The Story of Your Favorite Pokémon

What Pokémon can teach us about sentiment, attachment, and emergent play.

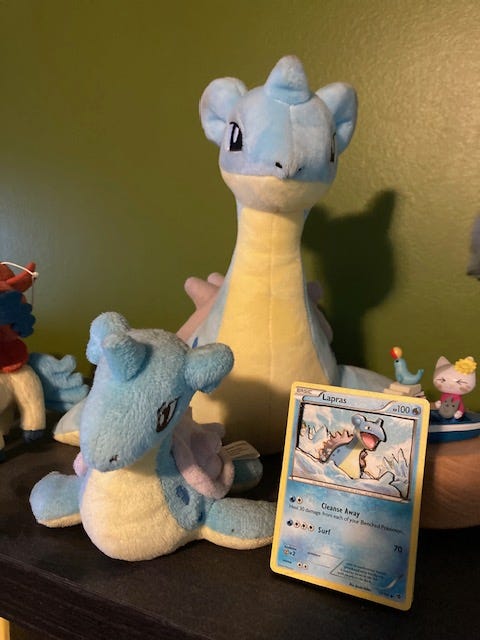

Lapras, My Beloved

There are a lot of reasons to be attached to a Pokémon. It’s commonly said that every one of the little critters is someone’s favorite, no matter how goofy-looking, weak, or forgettable they may appear to everyone else. My dear friend Eryn is a diehard Stunky fan.

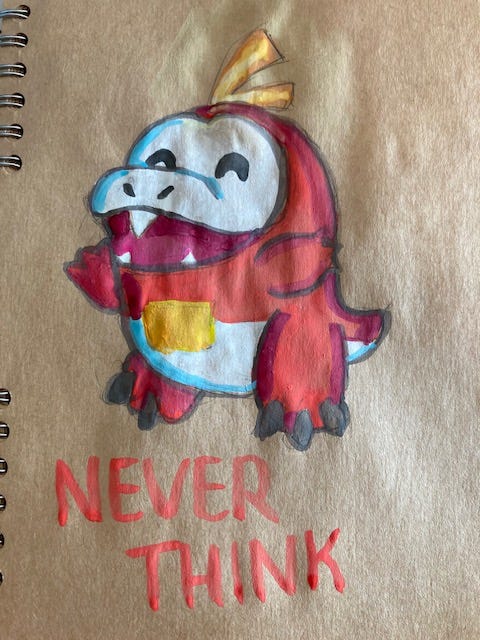

Sometimes, you make a favorite Pokémon because of their design. They’re certainly designed to be cool, or cute, or lovable, and their dex entries give just enough lore to spark an attachment. I call Fuecoco “my biological son” because I identify so much with its vacant expression, and find it charming to look at.

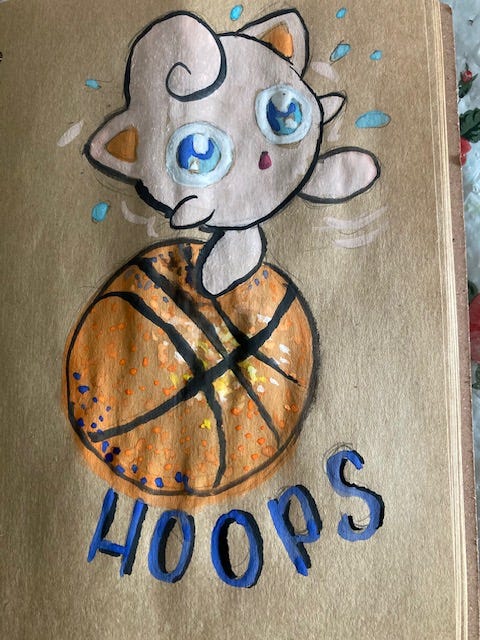

I also love Jigglypuff, because I identify a lot with a shitty little diva who wants attention and is willing to make it everyone else’s problem. Jigglypuff is a childhood favorite - I’ve loved this round little fuck since Pokémon was invented - it was part of my first gameplay, I traded eagerly for its card, and I laughed wildly when it threw its trademark temper tantrum on the anime.

But, my favorite of them all is #131, Lapras. Why?

Well, that’s the reason I’m writing this. Because, like many people, my favorite isn’t a matter of cuteness, or coolness, or comedy. My favorite is a matter of emergent gameplay. And, I think as game designers, even tabletop game designers, we could learn something from the way Pokémon provokes emotional investment in its game and its characters.

Mara’s Story

I was playing Pokémon Leaf Green when it came out in 2004. It may be tipping my hand a little bit, but I was 18 at the time. (As a lifelong fan of the series, I never missed a generation, even when my friends were outgrowing it.)

I was playing in my usual style, picking cute or lovely or rare Pokémon. I had childhood favorites Haunter and Kadabra, and a determined Venusaur. I truly don’t use any advanced strategy in these games, because they’re kids’ games so I just kind of let myself get sentimental.

Which is why, when I got the Lapras in Silph Co, I added her to my party immediately.

You see, natures didn’t exist in the first two generations of Pokémon. A “naughty” or “adamant” Pokémon wasn’t a thing, and had just freshly been introduced as a way to give the creatures a little individuality.

And Lapras, the Pokémon who was canonically the last of her kind in that generation, had a “lonely” nature. Even at 18, my heart broke for her, and I added Mara the Lapras to my party immediately so that she would have a friend.

And then, when Sabrina wiped my party out and only Mara was left, it turned out that no amount of Calm Mind will save you from a body slam from a plesiosaur. Mara repaid my kindness by being my last mon standing, and from that moment on, she was My Girl.

The Game Design

My attachment to Lapras is what game designers call “emergent narrative”. In other words, the game provided a set of outcomes that my brain stitched together into a story. Emergent narratives can be wildly compelling because of how organic and personal they are.

Lapras having a Lonely nature was a matter of random chance, as the game didn’t determine that beforehand. The battle against Sabrina was a matter of random number generation, as well as the combination of the AI and my own choices leading up to that point. There was no script in the game where a lonely Lapras repays a trainer for their kindness by fighting hard against an insurmountable gym leader!

That story happened only for me in my game.

Creating Attachment in TTRPGs

A lot of the ability of Pokémon to grab people’s attention is their adorable designs, so it’s easy for a game designer to despair and say that, if they can’t afford to hire an artist, they can’t generate that kind of attachment.

But, Lapras proves that there’s more to attachment in games than visuals. The OSR scene could also tell other designers a thing or two about attachment, investment, and random tables!

So, how could we recreate this kind of bond in a TTRPG?

Add personality by giving things names! The name can be the difference between “bog gremlin” and “Geebles, my best friend”.

Random outcomes with relatable options generate relatable outcomes! For example, “you find a potion” versus “Greebles finds a potion and gives it to you as a present.” If there’s personality in the outcomes on the table, even if it’s just one word like “lonely”, people naturally fill in the blanks.

Leave blanks for people to fill in! Let people decide how they feel about the outcomes, and build the stories in the gaps between your tables. Mara the Lapras never had a line of dialogue where she said “thanks for being my friend!”.

Stay out of the player’s way! Let them play the way they want to and pick up pieces of attachment on their own. This is how you make your emergent narrative personal.

One of my evergreen pieces of advice is to return to your inspirations and examine them closely. Even if your inspiration is a totally different medium than TTRPGs, by examining how you feel about them and why, you can find wisdom that connects not with a specific kind of game, but with people.

This was a part of my design process for Unspeakable Gate, and I think it really helped create a game a player can get attached to.

And if you want your emergent narrative to create a horrible door to scary land, check out Unspeakable Gate!